Originally published on Forbes

Over the past few years, the notion of Amazon-like consumer experiences and Uber-like business models has taken hold in conversations about digital health. This notion has become a north star for some, driving product strategy and billions in venture capital funding and M&A.

While Uber and Amazon have been wildly successful in creating entirely new business models that have disrupted traditional industries, these models have yet to demonstrate that they can be applied to healthcare.

Amazon In Healthcare

To start with, no one has yet come close to delivering an Amazon-like experience to healthcare consumers—including Amazon. It may be informative to review Amazon’s healthcare journey: In May 2020, Amazon launched Amazon Care, promising new service quality standards in online access to healthcare. At the time, I was one of many who hailed it as a big deal that heralded the much-awaited disruption of a broken healthcare system.

Fast forward two years: Amazon Care is shutting down operations (subscription required) and letting go of over 150 associates by the end of 2022 after struggling with scaling challenges (subscription required) and service quality (subscription required) issues. Amazon has remained committed to its healthcare market strategy and we may see a new approach arising from its planned acquisition of One Medical (subscription required), a provider of primary care services for close to a million patients from some 180 locations across the U.S.

The basic premise of an Amazon-like experience is that consumers will buy primary care services much as they would shop online. But this may be a flawed assumption. Let’s take the example of a doctor’s office visit. Traditionally, consumers dial the doctor’s office and schedule a visit after consulting with an office assistant or nurse about which doctor to schedule with, based on a quick triaging of symptoms over the phone. In an Amazon-like healthcare experience, consumers would be able to self-schedule the visit online, instantly, using online tools that triage the symptoms, match them to the appropriate clinician and pick a slot from a calendar, much like booking an airline ticket and selecting a seat.

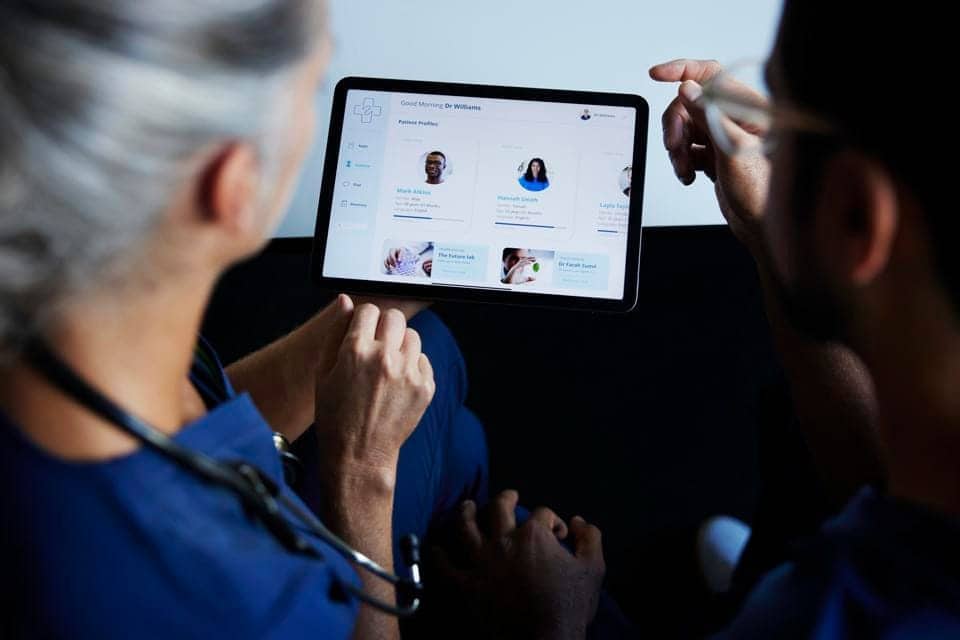

Previously in this column, I have discussed how far telehealth and virtual care models have come and highlighted headwinds to increasing adoption rates. One major issue: What appears to be the simplest of online features can be among the most challenging for healthcare providers. My firm’s research on digital health maturity among health systems has identified online self-scheduling as the patient engagement feature with the largest gap between expectations and performance. Reasons include providers’ reluctance to expose their calendars online, thus negating the purpose of the online scheduling tool. Of course, there’s much more to enabling seamless online access to care, including tight integration with backend electronic health record (EHR) systems for real-time access to doctors’ schedules and patient medical information. Many health systems are working hard on improving online access to care, and there has been significant progress overall, though we are still nowhere close to an Amazon-like one-click experience.

The Uber Model

To take another example, Uber’s business model is often used as a reference for improving healthcare delivery. The metaphor implies a future gig economy where consumers will receive care by seeking out qualified physicians and healthcare workers using an app, much as we would hail a ride to the airport. To some degree, this approach has been implemented by companies like Zocdoc that allow consumers to schedule an appointment with any physician based on schedules published on the app. The CEO of Signify Health, a home health company that announced recently that it was being acquired by CVS Health (subscription required) for $8 billion, explicitly referred to doctors on their staff as gig workers in the mold of Uber drivers. While the Uber analogy may be valid for certain businesses and services, the question is how far this can go. Would we as healthcare consumers want healthcare providers to operate in Uber-type transactional relationships, where the odds of meeting the same driver for the next ride are practically zero? In other words, do we want to trade an intimate, long-term, trusted relationship with one that completely depersonalizes and transactionalizes it?

Some may argue that the answer is yes. We are going through an unprecedented acute labor shortage (subscription required) that has impacted all levels of healthcare workers. The healthcare sector is also facing the prospect of losing millions of workers in the next few years. Given this crisis, there is undoubtedly a need to get creative with technology and staffing approaches to care and do so without compromising patient safety and quality of care.

Final Thoughts

The healthcare system today needs innovators who can build an entirely new model of care, much like how Google created search to transform advertising and AirBnB unlocked free bedroom space to transform hospitality. Many companies are trying to do just that, and VCs are pouring billions into them. However, efforts to superimpose a consumer business model that has worked well for e-commerce and transportation onto healthcare have not had the level of impact we might have hoped for. It may be time to rethink our reference models altogether.